MY FAMILY

THE BETA ISRAEL CURRICULUM

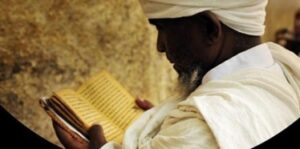

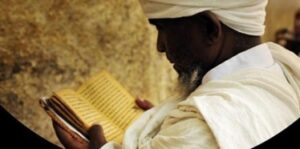

THE BETA ISRAEL AND BIBLICAL JEWISH TRADITION

Next, students should be asked to read the following paragraphs written by Rabbi Dr. Sharon Shalom:

“In all the research conducted about Ethiopian Jewry, one claim is pervasive – that the Beta Israel community was cut off from any halakhic development of Chazal (the sages of the Mishnah and the Talmud). In other words, Beta Israel was not influenced in any way by the formative events in the history of the Jewish people after the destruction of the Second Temple.”67

Thus, as noted by Rabbi Dr. Shalom, the religious identity of the Beta Israel community does not recognize the Mishnah or the Talmud (rabbinic writings). Rather, it is based on the spirit of the Tanakh (Bible) in its original teachings. While tradition throughout the Jewish world today draws from the Talmud and rabbinic halakha, the customs of the Ethiopian community draw from the teachings of the Orit68 (as the Torah is known in the Ge’ez language), the Nevi’im (prophets), the K’tuvim (writings), and the Apocrypha (the “hidden” biblical canon). The transition from biblical to Talmudic tradition in mainstream Judaism took place following the destruction of the Second Temple. The destruction sent shockwaves throughout the Jewish world, but had no influence whatsoever on the Ethiopian community, which remained unaware of it and continued to follow biblical tradition.69

Having read these excerpts, students should be asked the following three questions by selecting one of multiple choice options. Correct answer is marked with asterisks. (***)

- What religious Jewish texts existed approximately 2,500 years ago? – A) The Tanakh (Orit/Torah, Nevi’im & K’tuvim) and the Apocrypha (***) B) The Tanakh (Orit/Torah, Nevi’im & K’tuvim) the Apocrypha and the Mishnah C) The Tanakh (Orit/Torah, Nevi’im & K’tuvim), the Apocrypha, the Mishnah, and the Talmud

- What religious Jewish texts did not reach the Beta Israel in Ethiopia? A) The Tanakh (Orit/Torah, Nevi’im & K’tuvim) B) The Apocrypha C) The Mishnah and the Talmud (***)

- Looking back at our soup analogy, which Jewish texts do you think represent Group B’s chicken and matzah ball recipe? A) The Tanakh (Orit/Torah, Nevi’im & K’tuvim) B) The Apocrypha C) The Mishnah and the Talmud (***)

After confirming the correct answers to all three questions, teachers should explain that members of the Beta Israel remained steadfastly loyal to the laws and customs of their biblical Jewish tradition. Nevertheless, the message imparted by rabbinic authorities over the years (especially in Israel) was that to be “authentic” Jews, the Beta Israel must adopt the laws and customs found in the Mishnah and Talmud – which of course, their ancestors had neither known nor observed. This stance was evident in multiple discussions about Ethiopian Jewish practice and their halakhic status, including arguments over a responsa posed in the sixteenth century by Chief

Rabbi of Egypt David Ibn Zimra who had deemed the Beta Israel’s Judaism legitimate and asserted their descent from the Tribe of Dan. Unfavorable discussions to this regard emerged especially within the Israeli Rabbinate after the mass immigrations from Ethiopia in the late twentieth century (see Unit 9). For many members of the Beta Israel, the argument over their status as Jews was as absurd as Group B saying to Group A that their traditional soup recipe (passed down nearly unchanged for generations) was “inauthentic” because it didn’t include chicken and matzah balls.

Credit: Tel Aviv University70

67 Shalom, “Art as Experience: The Religious Culture of Ethiopian Jewry,” in The Monk and the Lion: Contemporary Ethiopian Visual Art in Israel, 17e.

68 It should be noted that the word Orit in Ge’ez literally means Torah, or the Five Books of Moses). The Torah scroll is placed in the sacred ark at the synagogue or in the home of the kes and is read on holidays and festivals. Some use the term Orit to refer to the entire Tanakh. The Tanakh of Ethiopian Jewry includes all the books recognized as canonical by other Jewish communities, as well as non-canonical.

69 Shalom, From Sinai to Ethiopia, 41

70 Photograph, Tel Aviv University, https://humanities.tau.ac.il/bible/bbl20